”The aim of physical preparation is to go beyond the level of motor ability that can be achieved by the sole practice of the chosen ability”

Michael Pradet

The only training that is certain to stimulate exactly the parts that makes up the full competitive movements and pathways for performance are training that is consisting of exactly those movements, performed in the same context as in competition. That is, doing the actual sporting events, and this is where training should start and what should always be included in a training program. But there is reasons for not only training the sport in specificity, such as the need for overload and variance. At some point we just can’t get better from doing the sport alone.

Training should certainly be designed to provide similarity when it comes to muscle action, cooperation, joint movements and energy systems as the movements performed on the field in the sport. But sport specific training should not only focus on physiological aspects of adaptation. Movement control needs to be universal because, possibly, of limited storage capacity for “motor memory”. Regardless of “size” of the memory, storing fixed sequences for all possible movements would certainly result in “choking”, because that would mean that you would have to find the exact match for the situation at hand before acting.

Instead movement seems to be structured by “patterns” so that the central neural system can let the body self-organize to a certain extent, and therefor fulfill both the need for speed to action and ability to handle variation in the environment where movement is performed. The same patterns would allow us the flexibility needed, for instance, to run both on grass and in sand.

Also, strength is not an isolated quality, but an integrated aspect of eventual performance. The ability to use a high number of muscle fibers in order to produce a a lot of force depends on how skilled or trained the athlete is in the specific movement.

There is a sort of “parental control” at work in order to protect the body from forces it is unsure that it can handle. A 100m sprinter can not be allowed to produce the same amount of force in a football game as when he or she is on the track. A football player have practiced to absorb the force produced when faced with the need for a sudden change of direction. A sprinter, who can produce force something like 6 times the bodyweight per leg, have not and if allowed to express this force on the pitch it would mean to risk serious injury

To cope with this, force production is linked to related movement patterns, not only in similar physical structure but also in similarity of sensory patterns (seeing and feeling) and intention. Exercises that are very specific to the sporting movements are very specific in all of these, but hard to overload without changing these sensory and intentional qualities. Movements that are easy to overload, are also very different and will therefor “unlock” less force production to use in the field of the sport.

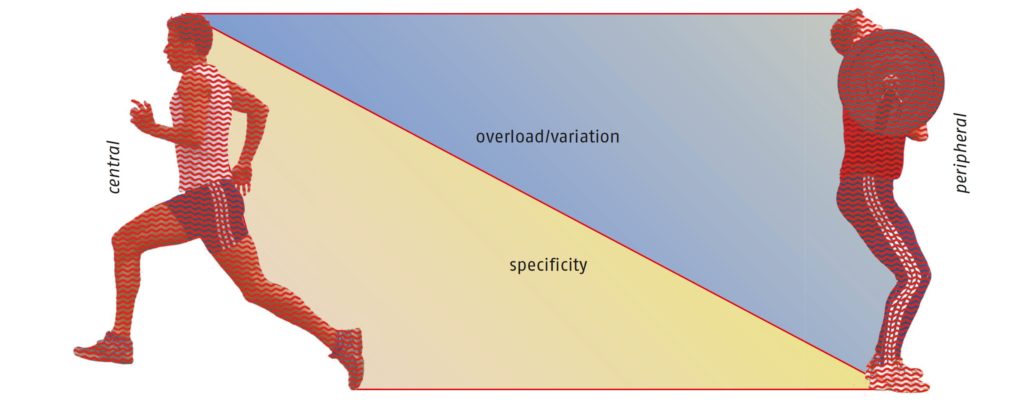

This line of thought concerning the role of coordination and learning in order to express force and power is outlined to great detail in Frans Bosch landmark book “Strength Training and Coordination”. In the book this dichotomy between specificity and overload is neatly presented in the image above, as the central/peripheral model, a problem that all coaches have to deal with. Then he goes on to notice that most inexperienced coaches spend a lot of time in the ends of the model, which is a safe starting point, but advising that more time should be spent in the middle zones of the model. A zone where both some similarities when it comes to those sensory and intentional qualities can be included, while still also offering some overload when it comes to force production of the muscles.

“Do you want to be strong, or do you want to lift heavy weights, they are not necessarily the same”

Jerome Simian

Last year I had the opportunity to listen to a presentation from the French coach Jerome Simian, who thinks in similar terms when it comes to movement quality. Jerome, who is the coach of Kevin Mayer – world record holder in Decathlon – talked about the importance of technical movement, the fundamentals of human movement that are common to all efficient movement patterns. He gave the advice that acquiring the ability to do a strict, perfectly coordinated, full squat will help improve the hip, pelvis and spine relationship. The ability to synchronize the opening and closing of these joints in order to maintain balance is one of the fundamentally common efficient movement patterns. The main point being that there is nothing to gain for an athlete, other than a powerlifter perhaps, in sacrificing perfect form for more weight on the bar.

Actually, too much time spent during strength training on movements that are not similar at all to the sporting movements, or performed in a synchronization between joints vastly different from the sporting movements can actually lead to a lowering of the performance in the sporting. This negative transfer can arise due to changes in coordination (from changes in muscle action and cooperation) or too much fatigue, no matter how much the athlete can improve the lifts used in training. And just because there is no general answer of “how much is too much” (and if there were this would also change with time), it makes good sense to prioritize keeping track of improvements in the sporting movements rather over whatever kilos someone can squat.

But back to the question regarding single leg versus double leg and heavy versus light weights. Both science and practice has repeatedly shown increases in various measures of sports performance with the inclusion of bilateral exercise in the training program. But single leg training too has been shown to do that. A caveat being that for single leg training this has, as far as I know, only been studied in untrained subjects. My own experience however is that, if done heavy enough, single leg training is also a potent stimuli for strength.

Learning from coaches like Frans and Jerome we start to get a good idea that we would like to

- Keep movement somewhat similar in movement patterns and stimuli

- Overload as much as possible while satisfying rule #1. Large load means larger neural adaptation and higher percentage of muscle fibers being recruited.

- But do not let the main movement mechanics break down or change during the set

Similarity should be sought in producing force using the same muscles, in similar directions. That means that I would argue for single leg movements for developing maximal leg strength for sports played on one leg (cycling, team sports, track and field, racket sports, etc) and double leg movements for those that have movements performed symmetrically (power lifting, weightlifting, CrossFit, etc). Similarity in sensory and intention in this context is obviously hard, but means mostly to have a clear, and similar, beginning and end of the movement.

Further, I would generally do these movements heavy: 1-5 repetitions per set, and I would not do as many sets as the athlete could do being cautious of unnecessary muscle-damage.

(Nothing should ever be set in stone and obviously what the athlete in front of me enjoy the most will also matter when making these choices, but we are talking general rule of thumb here.)

Still the main problem is that for “the reps that count”, the ones where we have to use our strongest muscle fibers, the mechanics are likely to change. But I think that there is a solution: a “hack of the system” to duck the problem with lack of balance affecting the movement mechanics. Regardless if this mechanical change comes from fatigue and/or intensity.

Hand assisting the movements allows you to provide just so much balance so that the movement mechanics are kept the same (maintaining good movement), but not too much to provide sufficient neuromuscular stimuli. Further, the help maintaining stability can be controlled and increased when fatigue accumulates. This might decrease the load placed on the body slightly, but – and this is important – to exactly the extent that you are capable of handling that very moment.

In many ways it seems to provide a perfect compromise in order to build maximum usable strength! So how could this look when it comes to strengthening the legs?

My two favorite movements are for this is the hand-supported split squat fathered by Fred Hatfield and Cal Dietz performed with the safety-bar.

The key is to not allow the hips to open quicker than the knee, and slightly “leaning into” the support makes this possible with quite heavy weights. This also provides the feeling of “going forward” which might provide som similarity to the sporting movement from a sensory information standpoint. Clear and distinct final position is coupled with an equally clear starting position, that could be varied with elevation of front or back foot.

If you have access to a flywheel training device then you can replicate my next favorite exercise that we call “old man with a stick”, which is similar in design just that using the belt makes it easier to really “go for it” with less possibility for a missed lift. And with the sticks it’s also not possible to “cheat too much”.

I quite like the relative balance of the trap bar and use that quite a lot too, but apart from that I haven’t used many other movements for the maximal strength of the legs (for sports played on one leg) in quite some time.

Fewer movements and less volume on “the far end” of overload leaves more time to work that “middle zone” that Frans Bosch talks about in his central/peripheral model. Movements that might not working maximum force production but still overload force produced and with more related movement patterns. Movements as (weighted) jumps, throws and weightlifting derivatives, which I think adds so much much both to transferrable force production and to include sufficient variety in training to avoid the stress of boredom and monotony.

Since implementing this line of contextual thinking for my athletes concerning their maximum strength work I’ve seen very good results on the field while doing way less of it.

I think it’s very easy for coaches to get stuck “chasing kilograms on the bar” and ending up thinking that every athlete should commit to a “starting strength” type of power lifting program in the weight room, where in reality probably not many should. A more efficient program might yield better transfer of force production, but still free up time for specific work in the gym or on the field.

- “Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrative Approach”, Frans Bosch, https://www.2010uitgevers.nl/products-page/sport-bewegen/strength-training-and-coordination-an-integrative-approach/

- “Building the World’s Greatest Athletes”, https://simplifaster.com/articles/building-elite-athletes-jerome-simian/

- “Why we focus on movement patterns before max effort”, http://aw-blog.com/sports-performance/strength-training/why-we-focus-on-movement-patterns-before-max-effort/

- “Unilateral Versus Bilateral Exercise and the Role of the Bilateral Force Deficit”, https://www.academia.edu/21886564/Unilateral_Versus_Bilateral_Exercise_and_the_Role_of_the_Bilateral_Force_Deficit

- “Supercharge Single Leg Strength with This Key Split Squat Variation”, https://simplifaster.com/articles/hand-supported-split-squat/