“Science gives direction to the forward movement; while art causes the actual progression. Thus a false activity of science inevitably causes a correspondingly false activity of art.”

Leo Tolstoy

Complementary strength and power training has been shown to be beneficial not only in power sports (throwing, jumping, sprinting, etc) but also in virtually all other sports as well, including team sports (football, rugby, ice hockey etc) and endurance sports (running, cycling, skiing, climbing, etc).

When developing strength training protocols for both team sports and endurance sports the emphasis is rightfully placed upon heavy and/or explosive lifting, because of the inherent potentially high neural drive of this type of training. Bodybuilding type exercises and repetition schemes are stressful on a molecular level, meaning that it might both stimulate undesired hypertrophy and that recovery is long and makes it difficult to combine with sport specific training.

This choice of emphasis often has the effect that coaches do not feel the need to address the exercise selection for their athletes more than to make sure that it provides a high mechanical tension in order to provide a general and abstract high neural drive.

While endurance and team sport athletes are not power sport athletes, and while strength training for them should be treated as general rather than specific, we still should seek to keep exercises somewhat similar in movement patterns and stimuli while providing as large overload as possible. Large loads and heavy weights leads to larger neural adaptation and higher percentage of muscle fibers being recruited, but heavy weights also contribute to change in sensory and intentional qualities and might therefor “unlock” less force production to use in the field of the sport.

When people are overwhelmed by choice and when they are anxious about it, they often turn to denial, ignorance and willful blindness.

Renata Salecl

Often when discussing strength training with endurance or field-sport trainers I am told that “we train deadlifts, because they triggers neural drive”. When I ask if, while being a great exercise, there could possibly be an even better one available for their athletes they usually point to the fact that deadlifts (or whichever other exercise is their catch-all solution) provides neural drive (which implicitly is enough) and that there simply is no need to overthink exercise selection in the weight-room.

With that same reasoning one could advocate to perform only biceps curls, if they would be heavy enough to stimulate increased central motor drive and elevated motoneuron excitability. The response to this is (of course) that, in isolation, “that would not be a great base exercise for cyclists or runners or football players, since it does not involve using the legs”.

My point exactly.

Apparently there are things to consider outside of only the amount of neural drive of an exercise. When taking this too lightly we miss out on the opportunities that might lie buried underneath an attitude of indifference.

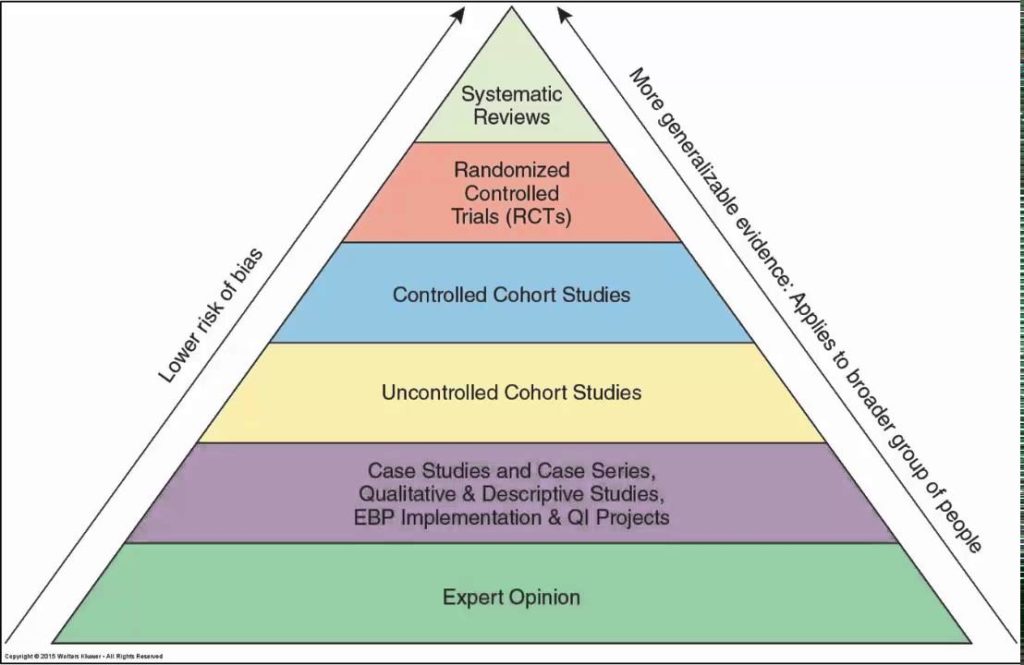

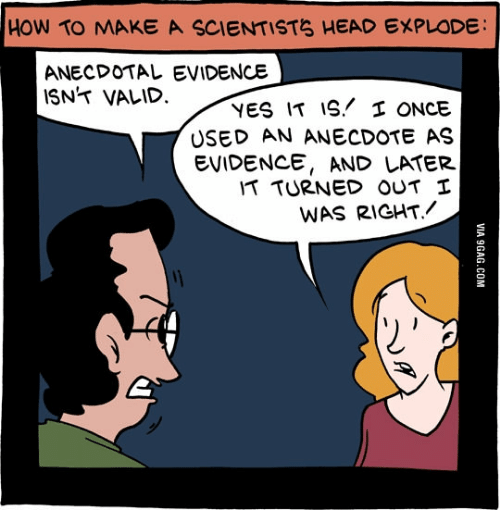

In science the expert opinion and the case study is regarded as the lowest type of evidence, as it can only tell you what worked or didn’t work for that one person, in that specific case. In order to say more general things we value science that includes data from more people, as this takes a specific context out of the equation. The more people, the better the prediction of a general average. When such studies also comply to certain standards (randomized and controlled, peer reviewed, published in high impact journals) they represent predictability which is highly regarded in the scientific community.

Systematic reviews and meta-analysis are considered to be the highest-level of evidence available. These types of reports consist of methods for systematically combining study data from several selected studies to develop a single conclusion that has greater statistical power, due to increased numbers of subjects, greater diversity among subjects, or accumulated effects and results.

It would be easy to interpret the results from such studies as the advances toward more and more exact knowledge, when they are in fact the opposite: more broad and general. They are great for predicting the average response in a certain situations, and if you want to be an average coach then you should only base your decisions on studies like these.

But I believe that being a coach should be about trying to beat the average, to be able to provide expert knowledge.

In the real world outside economic theory, every business is successful exactly to the extent that it does something others cannot. Monopoly is therefore not a pathology or an exception. Monopoly is the condition of every successful business.

Peter Thiel

When we accept that our selection of exercises matters, that we can do more than average, we face the risk of being overwhelmed by the sheer abundance of choices we have to make and therefore risk being “paralyzed by analysis”.

Not only that, but we also face the radical uncertainty of the large world: that we do not even know all the possible outcomes. It’s a world that cannot be described in the probabilistic terms of a game of chance because it’s not just that we do not know what will happen, we don’t even know the kinds of things that might happen.

I once read an anecdote about a decision theorist from Columbia University who was struggling whether to accept an offer from a rival university or to stay in his current position. Upon being urged by his colleague to apply his own models of rational decision-making in order to maximize his expected utility he responded with exasperation, “Come on, this is serious”.

To make statements about probability in the real world it is necessary to take into consideration not only the probability derived from the model, but also the probability that the model itself is true. And this we have no way of knowing. We are left to live in a world of unimaginable futures and unpredictable consequences that continue to call for necessary speculation and inevitable disagreement which often never will be resolved.

So when one has lifted ones gaze from the mechanical systems of the average, and now commit to adapt their actions to the situations they have before them, it’s all too easy to be overwhelmed by the sheer amount of options and the impossibility of knowing where the consequences end.

In these cases it seems that we have to remember that the consequences of an action are not everything that follows it forever (any more than the cause of a event is not everything that preceded it). These concepts are made to be used in actual cases where we converse about taking particular actions in our lives. We need to speak about particular circumstances and particular individuals, we need to not only use knowledge about the general (the knowledge we find in systematic reviews and meta-analysis) but also move back to the anecdotal, actual, world.

I do not know – if it matters I will try to find out

Mervyn King, John Kay

It seems we could get some guidelines on how to design complementary training exercises from looking at what principles that apply and what we can say is relevant to the particular situation and person at hand.

if we begin to look at the structure of movement we find that this motor dimension includes characteristics of movement within muscles, between muscles as well as force landscapes and external body posture and joint positions.

Within the muscles there seems to be very little positive transfer between shortening and lengthening of the muscle (concentric and eccentric muscle contractions) and reactivity (using pre-tensioning and energy storage and returning through stiffness). Also, if we are dealing with high intensity sports, the muscle needs to operate at optimal muscle-length and this too limits the possible transfer if training outside of this length when training in the gym (it could actually provide negative transfer if this optimal length is stimulated to change).

When looking at the level of cooperation between muscles the biggest concern should be if our sport carries with it the demand to co-contract in order to be efficient when going from slack to tense. This is usually the case in high speed sports, and if so merely adding load to a movement with the use of barbells or dumbbells should be questioned, simply because of it’s potential to reduce muscle slack as it may not challenge the body to learn to develop proper pre-tension with the use of co-contracting muscles.

Note that adding load likely has benefits, such as forcing the adaption to longer fascicles (able to contract faster than shorter), but we might do well to balance them with ballistic movements from a standstill, and perform some of our heavy lifting from a dead start if this is the case.

There are more ways to waltz, than to sprint

Frans Bosch

In his new book Frans Bosch “Anatomy of agility” discusses, amongst many other things, whether similarity in outward posture is the result of constraints from underlying levels or if it is a separate characteristics of specificity.

He argues strongly that posture is formed out of necessity from the inside rather than that posture shapes the internal movement landscape: given the pressure of time of high intensity movement and the ever-changing environmental influences the body is exposed to, it has to reside to as general principles as possible to be able to adapt. As information from internal force landscapes is more general, it may therefore be more suitable for this than information from posture.

If we look at “what is used in the field”, this is also a strongly rooted approach with expert coaches, who would consider it a bad strategy to first use only soft contacts when striking a boxing bag, hitting a ball or sprinting on the track and only later use forceful technique.

We might do well to no longer proceed our complementary training (or rehabilitation for that matter) from low-intensity to high-intensity, but rather choose to advance from large forces (with few degrees of freedom in movement) to large forces (with increasing degrees of freedom in movement).

- Train muscles predominantly similar to the demands of the sport (concentric/eccentric or elastic)

- If the demands of the sports is high speed and quick reactions do choose to limit the use of the stretch-shortening reflex.

- Do not mimic body positions, mimic force landscapes.

The endurance and field-sport coaches are right when they say that everything we do in the weight-room is by nature unspecific from what their athletes are doing “in the field”. But if we would consider these few points when designing exercises we would likely do better than average. Given that “we do not know what we do not know” I will always advice to do some, but not much, of the things we filter away as well – a smart contingency plan is a staple of good generals.

- Do a some very general things as well.

However this is only the physical perspective, we are still dealing with humans. Ask the person in front of you what they consider fun, and make sure to include some of that as well. A program of fantastic and smart exercises, is merely mediocre and stupid if you cannot get anyone to do it.

- If someone really enjoy doing something not following from the above list of principles, it is a smart idea to include some of that too.

- “Why too much choice is stressing us out”, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/oct/21/choice-stressing-us-out-dating-partners-monopolies

- “Averages are Meaningless (But, not always. Let’s explore where)”, https://towardsdatascience.com/averages-are-meaningless-7dfb9a7ef10c

- “Competition Is for Losers”, https://www.wsj.com/articles/peter-thiel-competition-is-for-losers-1410535536

- “Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart”, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227466812_Simple_Heuristics_That_Make_Us_Smart