The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown

H.P. Lovecraft

To stop the outbreak of the Corona virus we have radically changed almost everything we do: how we work, exercise, socialize, shop, manage our health and educate our kids.

We all want things to go back to normal. But what most of us have probably not yet realized is that it won’t go back to how it used to be in a few weeks, or even a few months. Some things never will be like they were at all.

Technology has been used quite extensively and successfully in some areas in order to work and to attend schools without gathering in numbers anymore, but the exercise industry has not been able to counter the sheer amount of loss of daily movement that the strategy of social distancing cause.

There’ll be some adaptation, of course: gyms could start selling home equipment and online training sessions, which is better than nothing, but will in no way be good enough to keep exercise efficient enough to carry the slack of the situation.

So, if not home or online training is the answer, what is? How can training be modified and used to handle this “new normal” in order to maintain physical and mental health and build healthy habits to keep us strong?

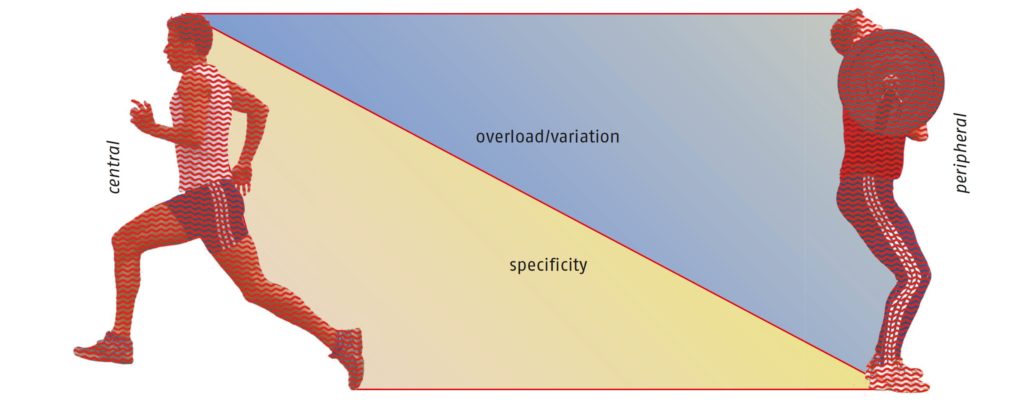

When it comes to the response to training there are clear individual variations in adaptations. While something works well to increase capacity for one person, someone else generally exhibit no meaningful improvements from the same training. An outcome that conventionally leads to them being labeled as “non-responders” to this particular type of training.

This use of language is problematic. First is the risk of promoting the general perception that exercise is not universally beneficial, and hence negatively affecting motivation for exercise. And something that is well established in science is that exercise has positive effects on health over a vast number of areas including reducing obesity, enhancing cardiac functions, reducing a large variety of disease states, improving function in life and improving mental health.

Secondly it could cause people to give up on specific modes of exercise prematurely, for instance thinking that “aerobic exercise does not work for me” or “strength training does not work for me”, when possibly it is exactly that type of training that should be carried out. However there is evidence that the number of non-responders is reduced when increasing exercise intensity and/or duration. This seems to be a useful strategy for lowering, or possibly even eliminating, non-response to training. In short: if you do it either hard or a lot, exercise seem to cause measurable adaptations in everyone.

A study in 2017 by Stanford University researchers using smartphone step-tracking data to map how active people in different parts of the world are analyzed data from 111 different countries found that Swedes took 6,000 steps per day on average while Brits took around 5,500 and Americans less than 5,000. Since walking is to be considered a very low intensity physical activity it will not have the same adaptations as more intense training, but it still form the backdrop of regular motion that forms the base of all movement that we do. More intense training adds upon that foundation.

Social distancing or all out quarantine radically decreases the amount of movement performed during normal daily routines. Most of the daily movement was done going to work and various social activities. Even if one was taking the car or the bus to work, rather than walking or biking, the vast amount of small movements within a day in society, as walking to the vehicle of choice, going for lunch with your colleagues and just to fetch “that cup of coffee” added more movement than is reasonable to replace at home for most people.

With large variations my best guess would be that something like 75% of regular movement have disappeared from most peoples lives. It’s not about that number – we can say it’s 50% – it is still likely to affect general well-being negatively when not doing a large chunk of the usual physical activity.

The body adapts to the environment it is exposed to, which is a good thing and something we use to cause adaptations to training. It means that we can become stronger and healthier! The opposite is also true, that without sufficient stimuli we can become weaker, sicker and more fragile. When we remove a large portion of our movement we expose ourselves to that risk.

The negative adaptation to that loss of movement won’t be something that we notice, but instead it will sneak up upon us. And with the realization that things won’t go back to normal for a long while we also must realize that this is something we need to tackle now, not later.

What’s true of all the evils in the world is true of plague as well. It helps men to rise above themselves.

Albert Camus

Society has evolved over thousands of years, so as to minimize the cognitive burden on individuals. And we call that minimization ‘habit formation’. We have developed rules of thumb that allow us to “just do” things that in our environment have been more or less constant. But when that environment changes, those habits no longer fit, and we cannot use the same rules of thumbs anymore.

So when normality changes it is also the time for us to rethink habit. It’s almost as if all these years you’ve been playing chess, and now someone comes along and says “Oh, now your queen moves like a pawn and the rook moves diagonally only”. Things that used to be almost automated now has to be cognitively decided. Those changes are difficult to process and confront.

Everyone wants to be healthier, but it’s very difficult to change habits. When doing so we are more likely to succeed if we impose gradual change that we can build upon, rather than a Draconian change of a large magnitude. It’s also about being able to decide to succeed: consider the difference between deciding to cut the caloric intake in half and to go to the gym three times a week. Restricting eating is something that has to be done all the time, continually throughout the whole week, whereas going to the gym is something that you just has to succeed with those few times. That’s why adding a few bouts of training are more likely to become habitual in the long run.

But like we established before, training has to be either high in load or high in volume and if we are replacing that vast amount of movement with just a few short sessions at the gym every week then it has to be rather intense. Intense here obviously means relative to the individual but “going for the heavier weights” when lifting or for the “intense and short efforts” when doing fitness. Rather than ending up doing 3 times 20 very sub-maximal reps to “get some burn”, instead opt for 4-6 reps where the last one is really, really hard. Ducking the “non-response” with 30 second sprints, with some longer rest in between them rather than going for that one longer slower interval (which could be an option if one would train more often and move more in the daily life)..

This is where home training, by yourself, through an app in your phone or with some kind of online sessions just won’t suffice in the long run. High intensity and high load training is very hard to maintain or frightening to start with on your own for most people. Social interaction and good coaching is often necessary in order to make training hard enough, in order not to be a “non-responder”.

My main point here is that people should, especially in this new normality, seek out a training facility, possibly where training is conducted in smaller groups managed by responsible and well educated coaches.

Doing so makes the step to get started minimal, and the possibility of success maximal: two things that largely benefit the habituation of training. I would suggest it to be some kind of “micro-gym”, since those have fewer members, minimizing risk of contagion while still offer social belonging and a multitude of social factors enabling you to train hard, while feeling safe and having fun!

Social distancing might be necessary in order to save lives, but they are also likely have consequences on mental health. In research conducted in China and Canada during the SARS-epidemic in 2003 found that a very large number of people that was quarantined came down with psychiatric diagnoses, especially post traumatic stress disorder. This risk was especially elevated for those with low incomes or at risk for unemployment.

Physical health benefits of exercise may take some time to happen, but where training seem to have benefits acutely is improving mental health, possible through providing some sense of control which could help to manage anxiety. A very important reason to not hesitate to keep training.

But is training reasonable during times of epidemic outbreak, or would it increase the risk of being infected, and if so, to participate in spreading the virus? Training has been shown to increase markers of inflammation, could this not be considered harmful and possibly irresponsible?

It is true that studies have shown that high intensity, intermittent exercise for relatively brief overall exercise time elicits a small inflammatory response. However physical exercise also promotes increases in the immunological function principally through anti-inflammatory response, so given a few weeks time the exposure to training have likely lowered the risk of getting sick, and with this you would be actively and successfully hindering further transmission.

Additionally, it seems that we can choose training intensity in order to mitigate the risk even from the beginning. Prolonged aerobic exercise induces a much more exaggerated inflammatory response than that of short duration high intensity interval training. So given the choice between lifting weights/doing a few sprints and adding mileage running track or road bike we might lean toward the former.

Another argument for seeking out that training facility with responsible and well educated coaches able to provide intensive training possibly conducted in small groups, because, and I repeat myself, doing intense training on your own is way harder than in a social setting guided by knowledgeable coaches.

The time to start to develop those habits for the new normal is now, not later. Things that we took for granted in society, things that are extraordinarily important for us, as human beings, human proximity and conversation and group living have been challenged. Hopefully, we will return to that again, but we might not.

A society more empirical, more analytical, more cooperative, more prosocial is something we should focus our attention towards today, maybe starting that process with a set of back squats at the gym or an all out sprint on the track?

- “Do Non-Responders to Exercise Exist—and If So, What Should We Do About Them?”, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329716455_Do_Non-Responders_to_Exercise_Exist-and_If_So_What_Should_We_Do_About_Them

- “Thinking Out of Equilibrium”, https://www.santafe.edu/news-center/news/transmission-t-004-simon-dedeo-thinking-out-equilibrium

- “The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence”, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30460-8/fulltext

- “How Your Mental Health Reaps the Benefits of Exercise”, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/what-works-and-why/201803/how-your-mental-health-reaps-the-benefits-exercise

- “Interim Briefing Note Addressing Mental Health and Psychosocial Aspects of COVID-19 Outbreak”, https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-reference-group-mental-health-and-psychosocial-support-emergency-settings/interim-briefing

- “High-intensity interval training induces a modest systemic inflammatory response in active, young men”, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3920540/

- “Short-Term High- and Moderate-Intensity Training Modifies Inflammatory and Metabolic Factors in Response to Acute Exercise”, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2017.00856/full