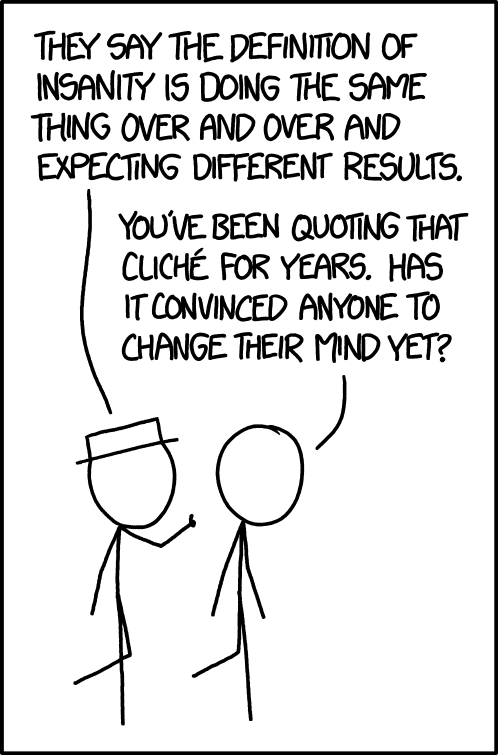

“The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result”

Because Einstein said it, it’s got to be true?

Well, first of all there is no substantive evidence that Einstein wrote or spoke the statement above. The linkage to the genius whose hair was always uncombed, clothing always disheveled, and who never wore socks occurred long after his death. It is one of many completely unsupported quotes attributed to him.

When one looks for the very influential statements’ real origins it seems like it originated in one of the twelve-step communities. Twelve-step programs are mutual aid organizations for the purpose of recovery from substance addictions, behavioral addictions and compulsions. Being communities who greatly value anonymity adds to the difficulty to identify a specific author to the saying.

Regardless of who first said what, the idea that one can try something and instantly see if it resulted in anything useful or not, is something that we mostly take for granted. From this we, usually without thinking much about it, similarly take for granted that if something did produce positive effects it would do so again if we kept doing it.

When doing so we fail to see that not all change and not all strains within a system are visible on it’s outside or by the parameters we measure it by.

Further it can make us rush on to try new things too soon. To give up when we would need to be patient and let the things we do bring about the change they could, given some time.

Systems can be analyzed in terms of the changes of their states over time. A state is an attempt to characterize, or define, a system by a certain set of variables. When a system changes its state its variables also change as a response to its environment and a completely different behavior might emerge.

This change is called linear if it is directly proportional to time, the system’s current state, or changes in the environment. They are called nonlinear if it is not proportional to either of them. In a nonlinear system very small changes might sometimes give rise to great changes of the system, and vice-versa.

Complex systems are typically non-linear, changing at different rates depending on their states and their environment. They have stable states, called attractor states. These are states that are preferred, and govern system behavior to stay the same even if perturbed. They could also be unstable, at which the systems can be disrupted by a small perturbation.

Examples of complex systems are the ecosystem, the weather, forests, organisms, the human brain, infrastructure, social and economic organizations (like cities) and ultimately the entire universe.

When these attractors are in such unstable states, exposure to what might look like the same environment, or such tiny changes of it that they can hardly be seen, could quickly completely change the entire systems behavior.

This type of change, which characterizes much of nature, is often abrupt and discontinuous. Systems experience periods of turbulence as attractors destabilize and create the potential for phase transitions (sometimes called bifurcations or tipping points). During these transitions, systems reorganize into new patterns of functioning.

A familiar example is the transition from liquid water into gas when boiling water. Under gradually increasing heat, the water remains liquid until the tipping point of 100°C is met and the sudden transition toward the gaseous phase takes place.

If one wanted to boil water but gave up when nothing happened after a minute or two, one would be prematurely looking for other ways to get things cooking.

Samuel Beckett, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, and most famous for his play Waiting for Godot. A play that was famously described by Irish critic Vivian Mercier as in which “nothing happens, twice”.

Two dysfunctional men encounter others along the road as they wait forever and in vain for the arrival of someone named Godot. They fill their idle hours with a series of mundane acts and trivial conversations as the world of the play operates on nothingness.

Surely the author of such a play could offer a counterpoint to the dominating “definition of insanity”? Something more useful to handle the everyday struggle of nothingness without prematurely abandoning or giving up on one’s efforts?

Sure enough, In 1983 Beckett offered a different perspective in his work Worstward Ho:

“All of old. Nothing else ever. Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

What Beckett is telling us is that no matter how good the attempt, all actions inevitably fail to be perfect, then one must make another attempt and another, and the effort is in the attempt – not in the product.

In a non-linear world one could be considered mad if one would think that doing the same thing over and over again could not produce a different result. For both the person and the environment where the action is carried out is always different, if only so subtly.

Possibly the hardest thing to do as a trainer is to back off. To realize that while you are very important in some parts of the process of learning, most of the time must be spent simply doing.

I have a friend who is a very accomplished trainer, and who have few superiors when it comes to designing exercises. His skillful eyes see not only unsatisfactory movement outcomes, but also at what point initial flaws that might be causing them arose. On top of that he has great understanding for manipulation of the exercise to open up for better movement patterns, as well as being skilled in communication.

We often teach together and his imagination and sharp eyes never seize to impress me. Then things go wrong. He’ll have the athlete do the exercise a few times, or maybe a week, watching closely. If he sees better outcomes, he goes on to take on the next pattern to be sharpened.

Change takes time.

Much like parents often end up trying to fulfill their dreams through their children, teachers often get too involved in the process. Over-coaching and pushing too quickly can be just detrimental to the development of new and efficient attractor states as the opposite.

In other words, it simply happens. The coach, the midwife of all those new skills, is simply momentarily assisting in the process, but not making it happen.

Practicing and performing require a quiet mind: a mind that is empty of expectations, ideas, and presuppositions, that is open to what happens in the presence of every aspect of a movement.

To be a masters trainer, on top of all your technical wisdom, you need to be patient.

- To see possible improvements and manipulate exercise in order for these improvements to arise.

- To communicate so that the student understands what constitutes a good rep versus a less good rep.

- Stepping away and letting the student find his or her way of increasing the frequency of good reps, until it is something done without thinking. The failed reps in the process is what eventually lets the good reps just happen. (very hard, and often forgotten)

- Staying cool and detached yet a little bit longer, remembering that just because some good reps are being done, it does not mean that they just happen, just yet. (requires the patience worthy of Buddha himself)

Coaches momentarily assisting the process I said… But sometimes that moment is long. One week? Four weeks? Months?

It is impossible to tell how long it takes for a new attractor state to emerge, but in my experience it varies not only between individuals, but also with time for the same person. All we have is to stay rooted in the present and to evaluate the fluctuations of the athletes results.

When an attractor is getting more stable there will be less fluctuations in performance. In order to see this we cannot vary the exercises and workouts too much.

A master coach who did take this to great lengths was Anatoliy Bondarchuk. A former Olympian himself, he turned to coaching after his career and is widely regarded as the most accomplished hammer throws coach of all times. He developed what can best be described as completely response-based programs. His method largely consisted of repeating the same session over and over again, with no wave loading of training variables and abilities, and no changes in strategic or qualitative elements.

Will there be no variance in such a system? Surely there will be, for in a complex world both the person and the environment is always slightly different.

A program with little variation allows you to see the states of the system over time. When data and form seems stable, then we can also assume that the attractor states are stable. When this happens, but not before, we should be increasing task difficulty in order to force adaptations via yet more phase changes.

One note of warning though – one might be tempted to think that we now know how this athlete responds to training, and would be able to predict the time to adaptation or phase transitions for the athlete. But when a system changes its state, a different behavior will have emerged.

While we now know our process of exercise selection and communication likely functions well for this athlete, we can’t ever relax and be the lazy coach.

“For the young the days go fast and the years go slow; for the old the days go slow and the years go fast.”

Anna Quindlen

Regardless of what specific method one adheres to, for there are many possibly great ones, one thing I see more from the experienced coaches is that they are likely to let things take their time and by doing so allowing for more possible growth of their athletes.

- “Insanity Is Doing the Same Thing Over and Over Again and Expecting Different Results”, https://quoteinvestigator.com/2017/03/23/same/

- “Critical Mass and Tipping Points”, https://fs.blog/2017/07/critical-mass

- “In which nothing happens, twice”, https://onartandaesthetics.com/2015/11/10/in-which-nothing-happens-twice/

- “Samuel Beckett – Inspirational Guru?”, https://www.londontheatre.co.uk/theatre-news/west-end-features/samuel-beckett-inspirational-guru

- “A discussion with Derek Evely and Matt Jordan”, http://www.mcmillanspeed.com/2016/02/a-coaches-guide-to-strength-development.html