“Only in failure, in the greatness of a catastrophe, can you know someone.”

E.M. Cioran

Picture some middle-aged dude with the habit of going down to the local wrestling club, always challenging the newcomers in the kids class to matches of greco-roman wrestling. He’s crushing them! Ripping them up! Throwing their little bodies in the air, slamming them back down on the floor, trash talking… He is 183-0 against them. He is the MAN.

Well, if Alexander Karelin, widely considered to be the greatest Greco-Roman wrestler of all time, would go down to the same club to wrestle the same kids he too would be 183-0 against those kids. If this was all that we had to go on to decide which is the better wrestler of our dude and the “The crane from Siberia”, apart from reverting into aesthetics, how would we ever know.

And how could our middle-aged friend ever truly know how good of a wrestler he is until he dares to challenge himself enough to fail, and therefore see where his limitations are?

Uncertainty is scary, but when you accept that uncertainty of things, the flip-side of that is that now you can go anywhere. If you accept the dangers of the Savanna, for example, you don’t have to stay crammed inside of that armored car on the road watching things from a distance.

But just like any experience that is quite special, it comes with a cost. And the cost of this type of existence is anxiety, dread, and all the rest of the feelings that come with plunging into the unknown.

For some to seek out, and stay, at these borders of what is comfortable comes completely natural.

For instance I remember meeting Dragos Stanica for the first and unfortunately only time in my life when I was teaching a Course for Eleiko in Brazil a few years back, while the Brazilian nationals in olympic weightlifting was held at the same venue.

Dragos, a former weightlifter, who represented Romania in the 1988 Games in Seoul, South Korea, now lives on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro from where he has his base, serving as the national coach for Brazilian weightlifting.

One of the nights, after the final day of competition, me and my colleague got Dragos by our table and when we got him started talking we never wanted it to end. That man had so many great stories from his life to tell, and it seemed all we had to do to enjoy them was to keep getting him (and us) beer.

He told us about his life, from his upbringing in a poor Romania, how he got to be a successful weightlifter, got recruited by a circus traveling the world, to stories on how he became the physical trainer for most of the Brazilian UFC superstars, and it just kept going, all the way into how he now lived permanently in a Brazilian favela, helping kids to learn to overcome their environment with his little weightlifting club as his teaching tool.

Of all the stories he told, the one I most often think back upon is the story of him starting weightlifting. He was 13 years old when he first ventured into a weightlifting club located in a basement.

“The lightest barbell they had was permanently loaded with 50 kilos, and I barely weighed more than that”, he said, “they showed me other lifters snatching it, and I wanted to do the same, but I failed miserably of course”.

He went on to give a picturesque description of how he came back, week after week, month after month, always failing to snatch the barbell from the floor over his head. It all seemed completely futile of course, but it became an obsession to him.

“And then one day I snatched it. I was very surprised” and he took another sip of the Brazilian beer, looking as happy as he must have been in that basement on that day so many years ago.

”If to describe a misery were as easy to live through it!”

E.M. Cioran

But most people are not like Dragos, not even if they are elite athletes. Faced with the possibility of failure, many might rather walk away from the challenge completely if not helped by someone to stand firm in a sudden storm of emotions.

For infants, all signals from the body or the world around them are causes of panic and result in screaming because they have not yet learned to put them into words.

With the help of its surroundings, it then trains itself to interpret both it and itself, and many things are then no longer perceived as threatening. This allows the child to move on and make wiser decisions. The screams are exchanged for productive responses.

But that presupposes that it has not been trained to shout when it is just hungry or experiencing something else normal.

That, in turn, requires the help of responsible adults.

Anxiety is an integral part of performing in sport for a majority of athletes, regardless of what level they perform. Being able to manage that anxiety can really help to produce a better performance. Under pressure, some athletes can produce a “peak performance” where they actually perform better, but the risk to be overcome with nerves is also always present.

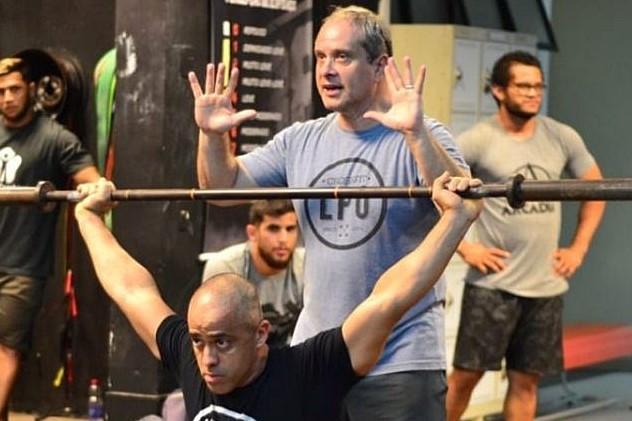

This, in my mind, is one of the most important tasks of the coach: to help and guide their athletes to dare to challenge themselves, to dare to stay in these uncertain situations despite the flush of emotions that may overcome them. This is hardly done by pretending that those emotions aren’t real.

Many times I have seen trainers reassure their athletes when affirmation more likely was what they needed from them. One situation comes to mind, in the warming-up area for the European Regionals of CrossFit in Madrid. I was there coaching team CrossFit Nordic in their pursuit to put them on the podium of the competition.

Arriving with the team to the warmup-up area to get ready for our first event, I saw this Swedish athlete who I knew, running and looking unhappy on one of the non-motorized treadmills. Knowing that the first individual event wasn’t until all of the team events finished up, I walked up to her and asked what she was doing there and where her coach was.

“I don’t think I can compete in the next event, I don’t think I am good enough” was her reply, and you could see in her eyes that she felt both scared and lonely.

After some time her trainer appeared, and I overheard his answers to her expressing her doubts of herself as “Come on, you’re great, you’ll do fine, stay strong!” and I watched her try to smile and to look strong.

This athlete quit individual competition after this Regionals, which was the athletes first.

Maybe this would not have happened if the coach, instead of trying to sweep the feelings of doubt under the rug, would have affirmed those feelings, helped to put some words on them, asked if she has felt like this before, if so what she did, and how that felt.

To tell her that it must be hard, but nevertheless normal to feel this way.

Anxiety is a state comprising both physical and psychological symptoms due to feeling apprehensive in relation to a perceived threat. Each individual may experience anxiety slightly differently and it also may differ from situation to situation. For example, one Olympic weightlifter I worked with couldn’t get themselves onto the platform without feeling like passing out, while many CrossFit athletes would be physically sick waiting in line for their heats, or cyclists frequently abandoning longer and tedious races, not because of tactical reasons, but overcome with feelings of doubt.

It is natural when experiencing anxiety to want to get rid of the feelings because they are unpleasant, therefore people can seek solutions to avoid feeling like that.

If the anxiety becomes extreme an athlete may even get to the point where the only way to not feel like that is to stop competing or even quit the sport. This is a solution, as it might put a stop to these strong unwanted feelings, but the athlete might by doing so lose what’s most important to them (their sport).

A better option would be to accept anxiety, embrace it and learn ways of living with it.

Using only reason and empiricism to do this will for some always fail, for these methods can not explain reality with certainty. Then, to be able to cope with this uncertainty, one must accept that the aversions causing these feelings are real and that they are felt in this way, rational or not.

Letting them be real, then look around to see the things, in the same situation, that are experienced as positive. While some things are outside of our control, uncertain and in many ways terrifying, some things are always not.

Continually doing so the floods of emotions experienced in these situations will be decreasing with time. The wolves that hunted you become dogs, in time they might even bring you your slippers.

– But I believe what you are experiencing is a feeling.

From the movie “The Party” (2017), Directed by Sally Potter

– It’s a horrible feeling.

– I can see it’s unpleasant.

– But like all feelings, it will surely pass.

This should not only be in the competitive setting. It has to start in the training hall, where one should not “win all workouts”. I am a huge believer in not pursuing perfection, for perfection is impossible to catch.

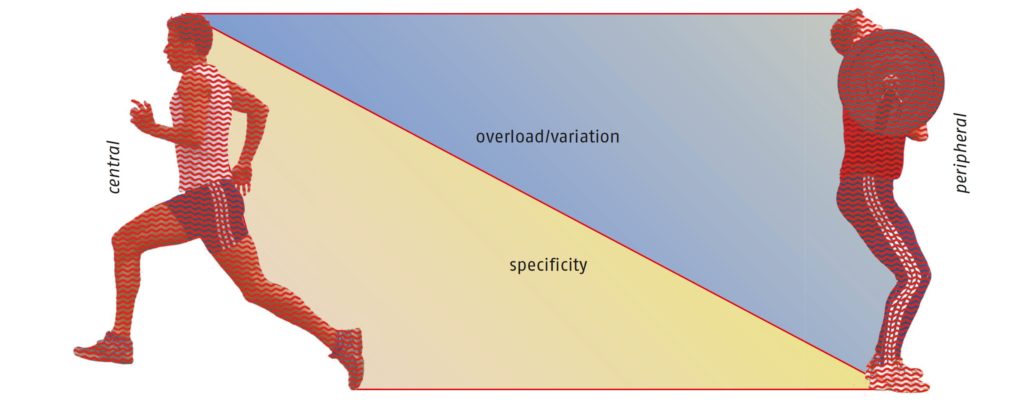

I have in previous posts argued that long periods of basic training has drawbacks when it comes to effectiveness and planning, producing unwanted adaptations, such as significant decreases in power and speed abilities, and taking up a lot of the training time available.

But these are not the only pitfalls of excessive periods of basic training.

First, the high intensity movements used in competition give the body fewer options to cope than using pre-tensioning strategies available through the stiffness of the muscles tendons. The lower intensity of basic training allows for, and it usually is done to strengthen the muscles contractile tissue.

But with less demands on the tendons, we risk that they become inefficient and come game time, when the luxury of inefficiency is not available leading to injuries (which put a stop to everything).

Second, getting back to my main point: if training looks too much like competition it becomes unbearable, or at least it does not provide enough variation to provide the means for improvements. But on the flipside, if it looks too little like competition it has no way of helping the athlete to cope, “learning the language of”, the uncertainty of competition.

Instead of more is more-approaches, where more necessarily means further from the demands found in competition, I once again propose a different not more-strategy.

Continuously challenging the individual participant by progressively increasing task difficulty during practice enhances motor learning and optimizes performance, while also helping the athlete to safely develop strategies to counter the frustration of being exposed to the slight possibility of failing.

“Failing to plan, is planning to fail”, and while this is good advice, as a coach you need to remember that the experience on the competition floor often is a very different experience despite all the training that precedes it, which often gives rise to emotions not able to plan for.

The way of being a better coach then turns out to be pretty similar in the training hall and on the field of competition: to take one’s nose out of the plan and look at the situation at hand.

- See possible improvements for each athlete and manipulate exercise in order for these improvements to arise.

- Do not reassure. This discounts the athlete’s fears, makes him doubt himself even more and reinforces the anxious behavior that got your attention. Avoid acting on your first impulse to counter them by reason. Instead: listen and confirm that feelings of anxiety, fear, doubt are normal.

- Do not say what an athlete should not do or cannot do (Such a list would be virtually endless and quite useless). Focus on communicating what he or she can or should do.

Experts in all fields appear fluid and natural but in reality they have made conscious efforts to shape the way they perform. Simply having the same knowledge of how to perform exercise is not what makes great coaches great.

If so many people know how to do a barbell clean and the basics of how to coach it, why are some so good at developing lifters and others are not?

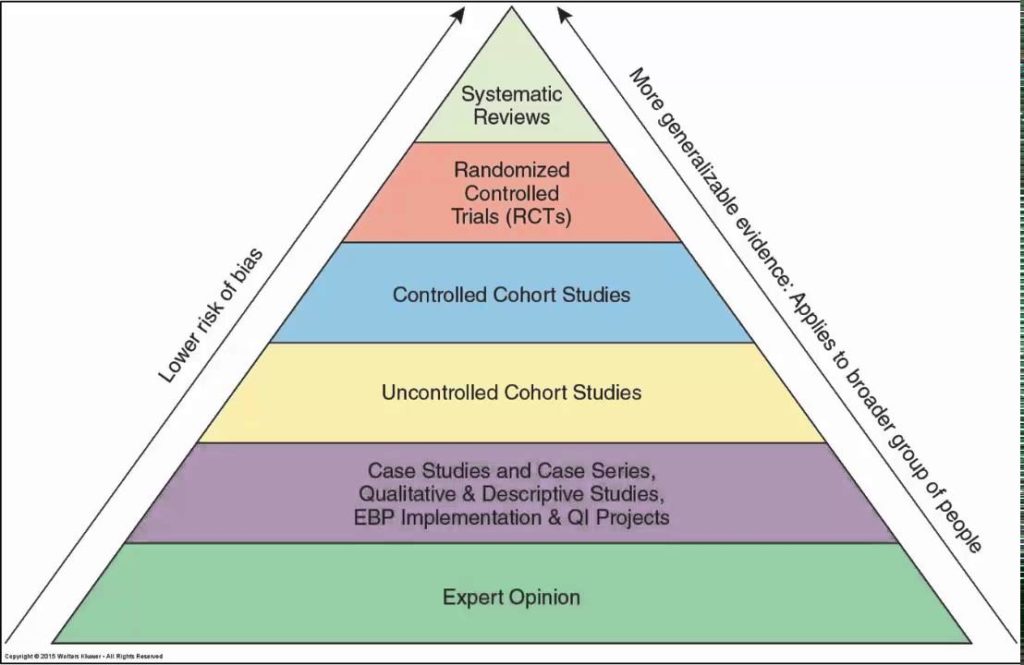

Science is great for predicting the average response in a certain situation, and while this is a good starting point that is all it is. The great coach also realizes that they are working with humans, with all the unpredictability and erratic behavior that might follow from that.